Robert Morris: Para-architectural projects

Curated by Sarah Watson

October 11–December 1, 2019

Opening Reception: Thursday, October 10, 7–9 pm

Hunter College Art Galleries

Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery

132 East 68th Street, New York, NY

Gallery Hours: Wednesday–Sunday, 1–6 pm

Hunter College Art Galleries are pleased to announce Robert Morris: Para-architectural projects at Hunter’s Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery. Robert Morris, who died in November 2018, was an alumnus of Hunter College and a member of the faculty for over 40 years. Hunter’s exhibition focuses on a series of large-scale drawings made by the artist in 1971, many of which were first shown in Morris’s infamous Tate Gallery exhibition of the same year. The Tate’s catalogue describes that exhibition as “a sequence of structures which, although they resemble in their uncompromised simplicity Morris’ earlier sculptures, invite physical participation of the public.” The interaction that Morris encouraged, however, ultimately resulted in visitor injuries as well as damage to the structures, leading to the closure of the exhibition only four days after it opened. In 2009, in collaboration with the artist, the Tate Modern reconceived the 1971 exhibition: this reinstallation, Bodyspacemotionthings, included newly designed versions of the participatory structures, but none of the drawings.

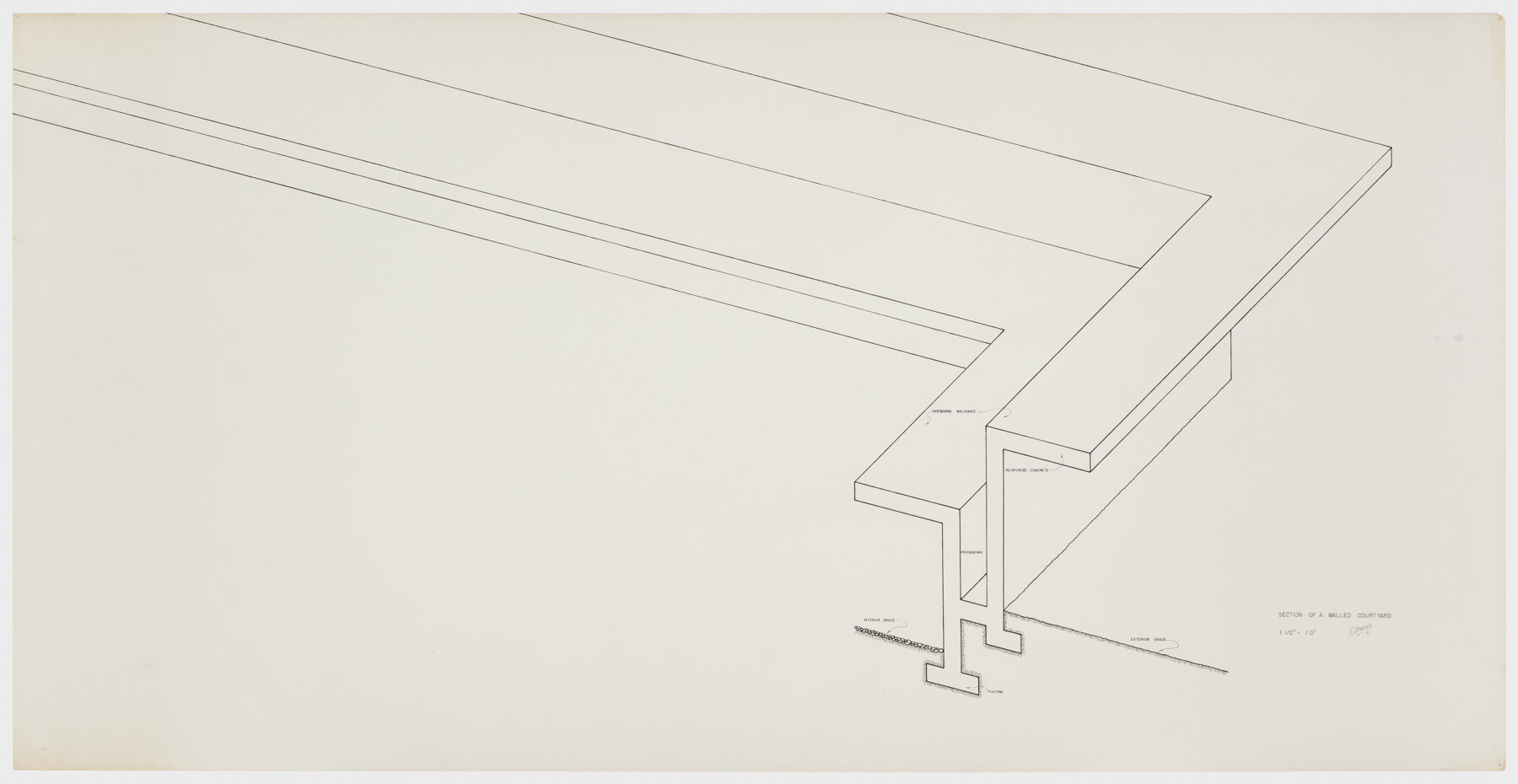

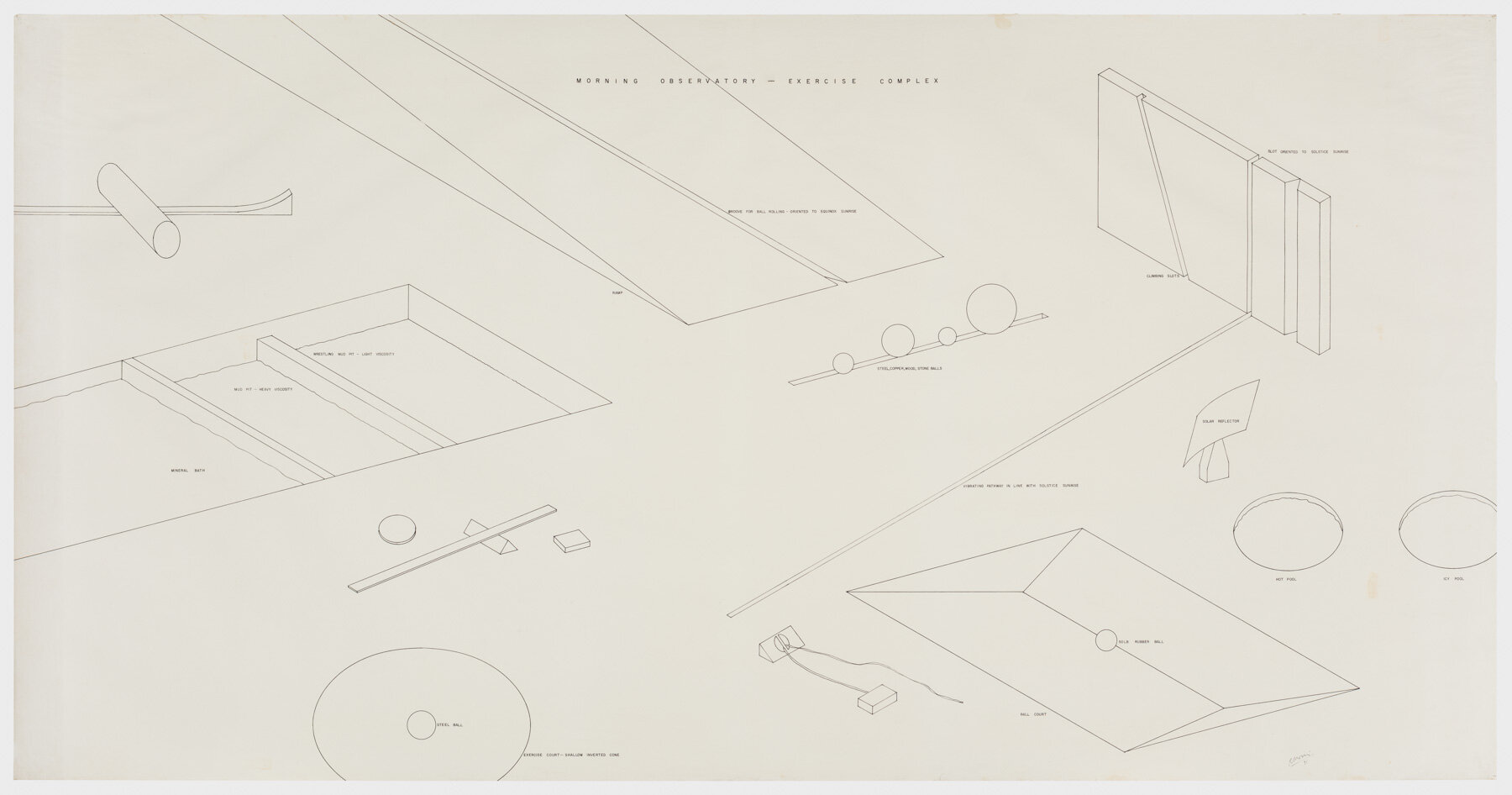

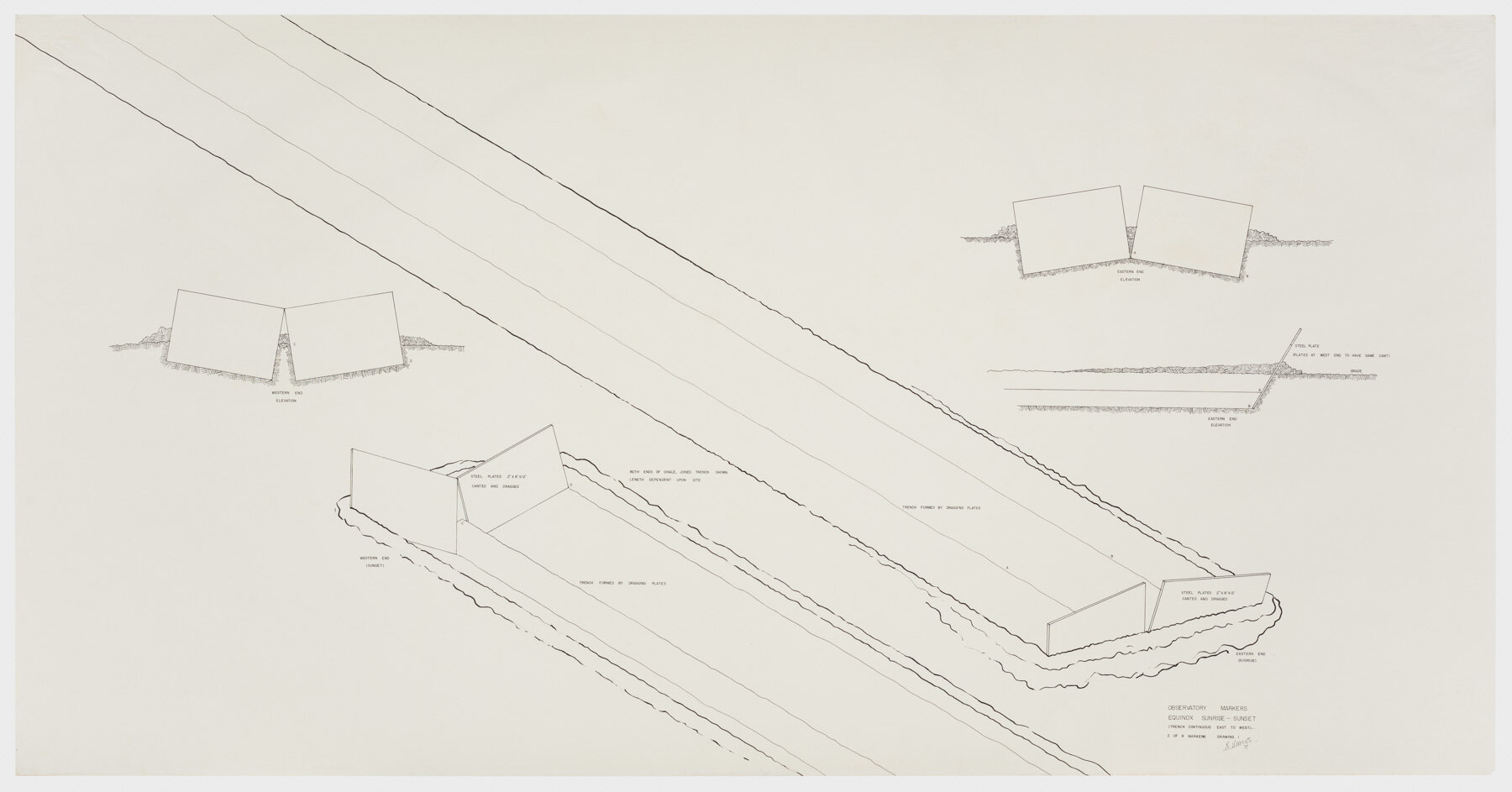

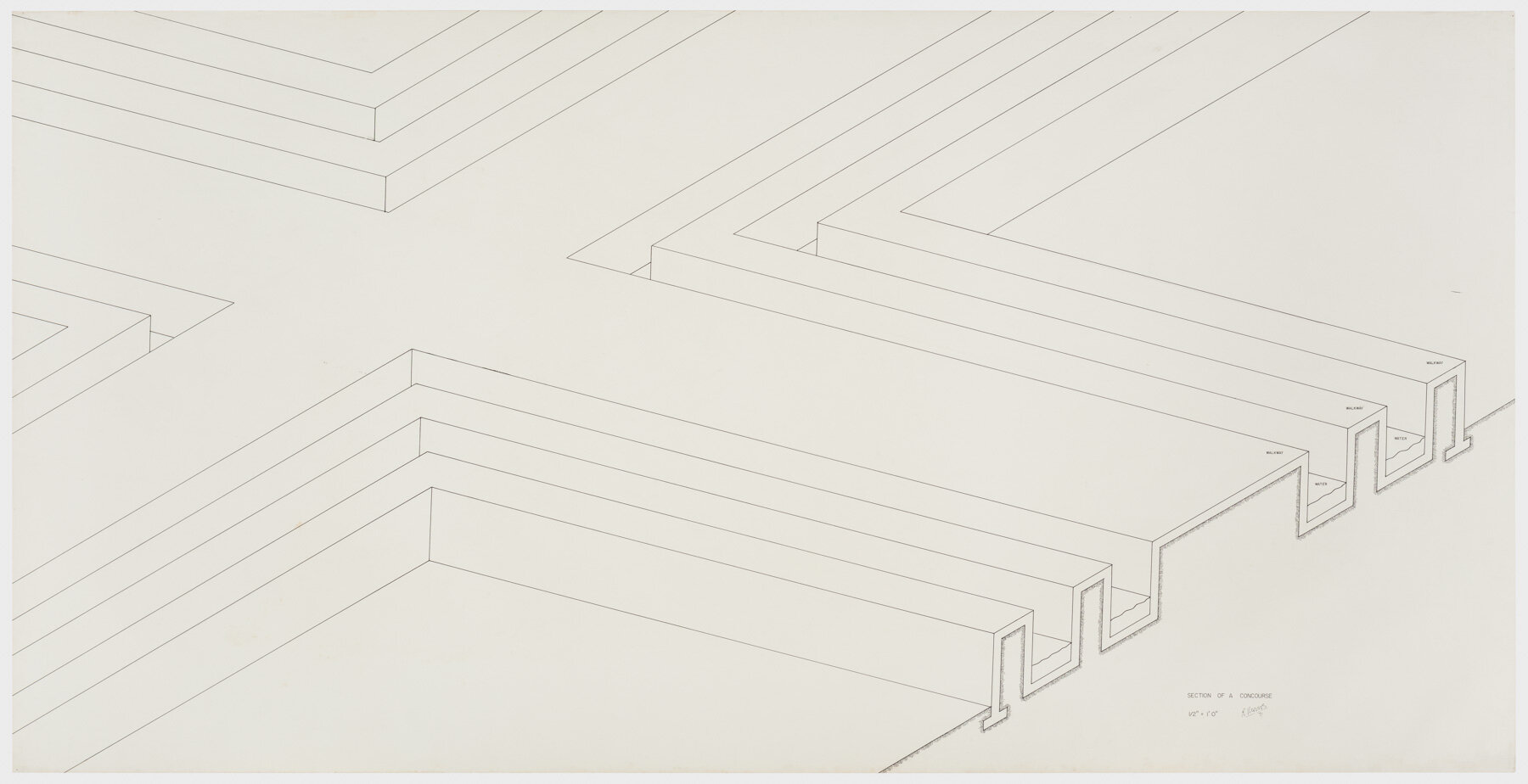

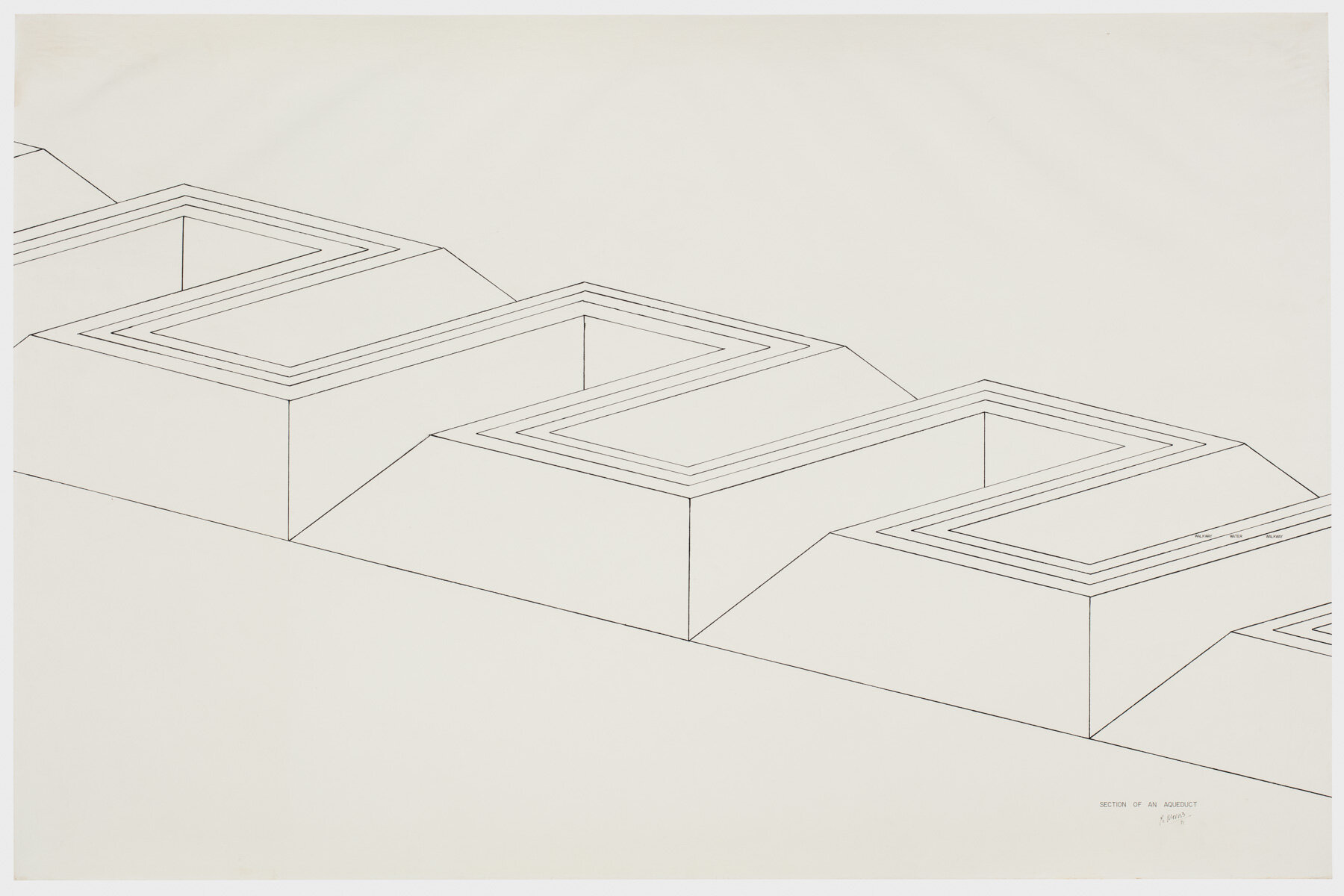

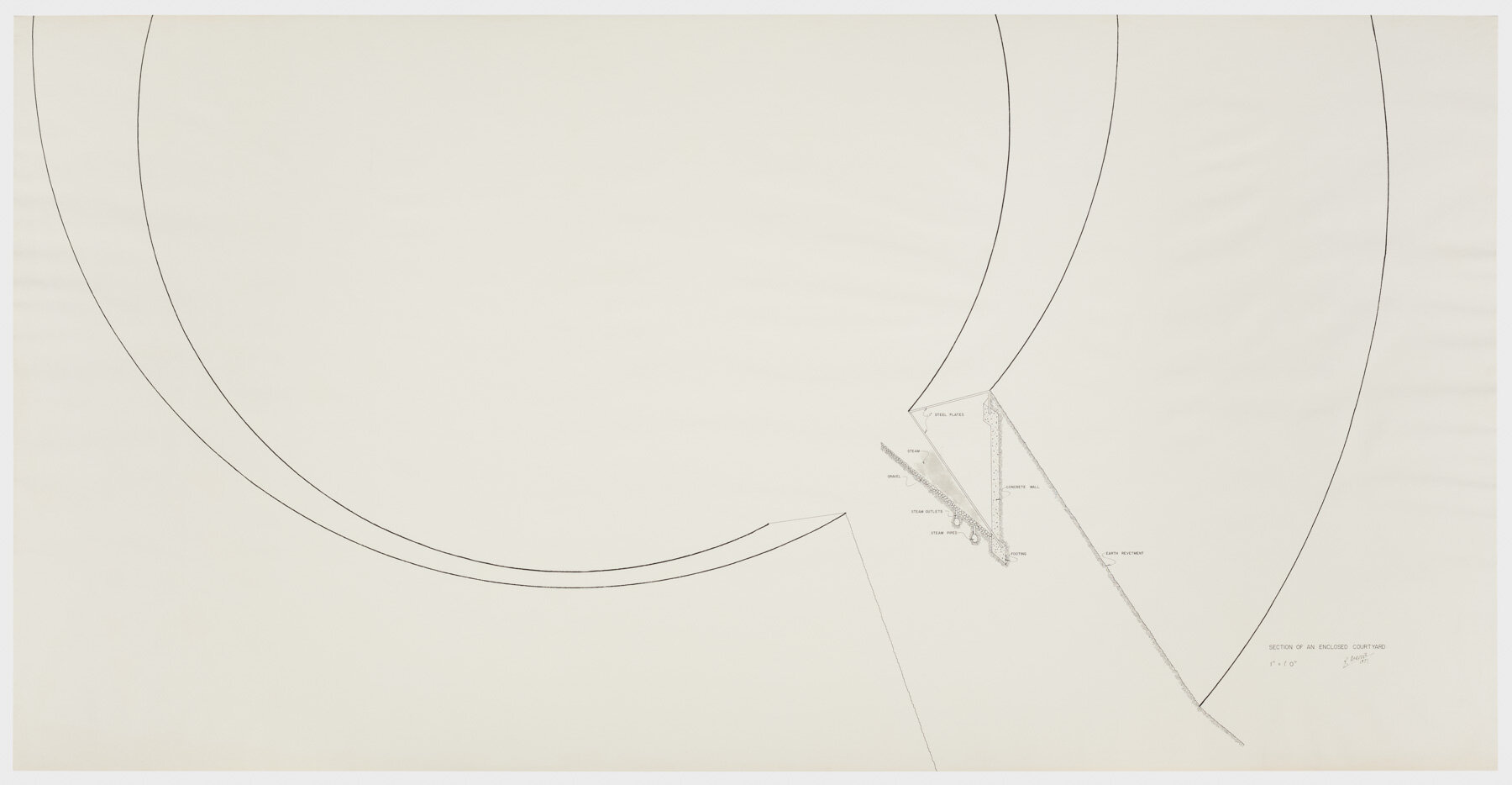

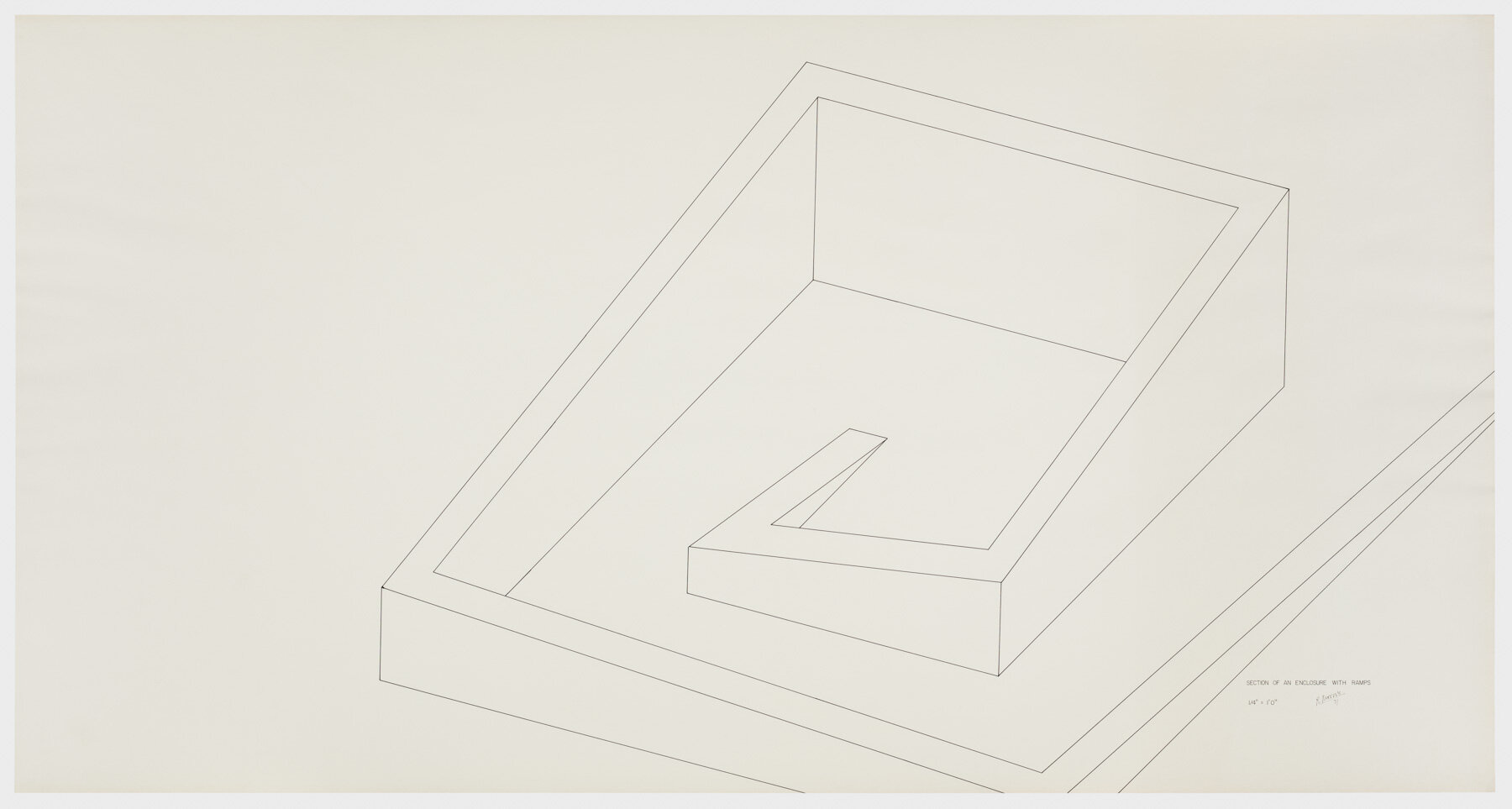

The Para-architectural projects —observations, exercise courts, aqueducts, courts, concourse, etc., as the drawings are titled in the 1971 Tate Gallery catalogue, comprise some twenty very large, ink-on-paper drawings that illustrate a fantasy architectural complex. The exhibition at Hunter brings together a selection of these drawings, including a work from Hunter College’s own collection, Section of a Walled Courtyard¾on view for the very first time. While Hunter’s drawing has not been exhibited previously, several of the other works in this series were included in exhibitions during the mid-to-late 1970s and early 1980s in Europe and the United States. Among these exhibitions is The Drawings of Robert Morris, curated by Thomas Krens at the Williams College Museum of Art in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1982. The publication for this exhibition has proven invaluable in identifying a number of these drawings as well as in gaining insight into Morris’s thinking about these works:

I have a persistent and recurring fantasy of a complex of spaces, forms, and functions. The temple-tomb complex of Djoser, the Great Stupa at Sanchi with its changing levels and promenades, the ramps of Hatshepsut, the enclosures, pools, arcades of Gopura or Angkor Wat, the great court at Ibn Tulun, Stonehenge and the observatory at Jaipur, the vast but human scale of unfolding spaces, gates, and enclosures of the Imperial City in Peking, the Sung bridge and pond of the Shen Mu Tien, the amphitheaters of Muyu-uray, the grim Mayan Ball Courts at Copán, the siting and forms of the American Indian works in Ohio, the troglodytic complexes at Luoyang or the kivas of Mesa Verde, the pavilions and levels and climatic considerations of Fatehpur Sikri, the militaristic revetment, escarpment, glacis, the zig-zag rampart of the fortress of Sacsayhuamán above Cusco, even the parade grounds of Nuremberg. . . . Neither religious nor militaristic the fantasy complex circles around a secular re-entry to time, place and function. In the Bath House Observatory one could soak and know precisely the location of that ultimate source of energy that has heated the water. One could work out at dawn in the Morning Exercise Court (the T’ia Chi used to be practiced at dawn outside the Altar of Heaven in Peking), one could walk for miles along the top of the meandering Aqueduct or wade barefoot in one of the shallow raceways on a summer day, take a snooze under the overhang of an Enclosed Courtyard, meet friends on a grand Concourse, that was not in the Bronx, check out the Solar Furnace Observatory on a bright, cold day, run up and down the ramps that connect the endless, interlocking Courtyards. I’m waiting for an enlightened W.P.A. to build this complex.

These drawings also connect to Morris’s Observatory, a large earthwork completed in Arnhem, the Netherlands, as part of the exhibition Sonsbeek 71 in 1971. In the show’s brochure, Morris posits in a short text titled “Observations on the Observatory,” that the “Observatory is different from any art being made today. It has a different social intention and esthetic structure from other art being made at present. I have no term for the work. A kind of ‘para-architectural complex’ would be close but awkward.” He continues that this concept “derives more from Neolithic and Oriental architectural complexes. Enclosures, courts, ways, sightlines, varying grades, etc., assert that the work provides a physical experience for the mobile human body.”

The drawings presented in Robert Morris: Para-architectural projects connect to Morris’s sustained interest in ancient and primarily Non-Western architectural forms, and to his concerns with presentness as an intimate experience in which physical space and “an ongoing immediate present” are bound. In turn, the exhibition at Hunter offers an entry point to consider what Morris might have meant by the “fantasy complex circles around a secular re-entry to time, place and function.”

Robert Morris: Para-architectural projects is made possible by the generous support of Carol and Arthur Goldberg, The Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation, the Joan Lazarus Curatorial Fellowship Program, the Leubsdorf Fund, and Castelli Gallery. We also extend a very special thanks to Barbara Castelli for her invaluable assistance with this exhibition.

ABOUT ROBERT MORRIS

Robert Morris was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1931. In 1959, Morris moved to New York City, where he met John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, and La Monte Young. At that time, Morris created his first large-scale sculptures, and played a central role in the development of the Minimalist Art Movement, emerging in the early ’60s principally from the stable of artists of the Green Gallery on 57th Street. In 1967, Morris created his first “Felt” pieces, which were exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1968. This same year, in his seminal essay “Anti-Form” that appeared in Artforum, Morris articulated his growing interest in the concept of “indeterminacy” which argued for an art that is based in process and that advocated chance and other organic processes in the creation of minimal sculpture.

Robert Morris has been the subject of numerous museum retrospectives at institutions including the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, DC (1969; traveled to the Detroit Institute of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York); the Tate, London (1971); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1994; traveled to Centre Pompidou, Paris). The artist’s work is included in major public collections worldwide, chief among them the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Art Institute, Chicago; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; and the Tate Modern, London.